A flag hanging on the Tabernacle ceiling with an illuminated 45th star signaled Utah’s admission as a state.

Credit: Courtesy of the Utah Historical Society

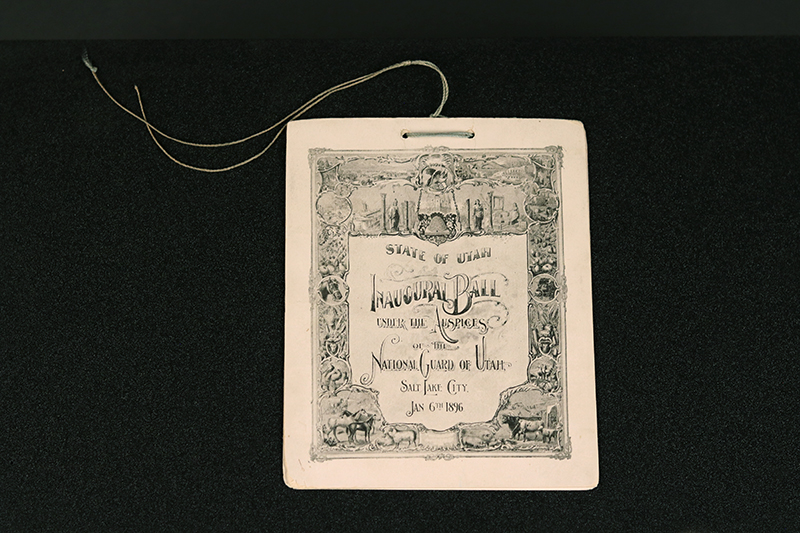

January 6, 1896

How Utah Celebrated Statehood

A Western Union agent ran into Salt Lake City’s Main Street and fired two gunshots into the air. That signal let Utah residents know a telegram had arrived from United States President Grover Cleveland. It was 9:13 a.m. on Jan. 4, 1896, and Utah had been accepted as the union’s 45th state after a tumultuous nearly five-decade political campaign, the longest territorial period for any state.

Announcement

Proclaiming an Achievement

Achieving statehood required Utahns to overcome long-running fights with the U.S. government. That included charges of Utahns’ disloyalty to the union, which led to an early armed standoff known as the Utah War, as well as a later federal law disincorporating The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for the practice of polygamy, which also stripped established voting rights from the territory’s women.

Charles C. Richards, acting governor of Utah Territory, proclaimed the next Monday as Statehood Day. He ordered schools and businesses closed on January 6 so residents could celebrate “in a manner becoming a free, intelligent and patriotic people,” according to his proclamation published on the front page of Salt Lake City’s weekly “The Broad Ax,” one of several Black-owned Utah newspapers.

The news spread across the state quickly. That Monday, residents woke up to a “din surpassing anything they had heard before,” wrote Audrey M. Godfrey in “All Hail! Statehood,” a 1995 Utah Historical Quarterly article. That noise was made by “guns, whistles, and bells of every variety” as well as “anvils, dynamite, yelling, singing, drums, and bands for two hours and then intermittently throughout the day.”

One Utahn labeled the racket "bedlam," while a newspaper reporter termed it "hilarious pandemonium." “Like Fourth of July in winter,” another reporter proclaimed, as Utahns spilled out into town streets on a sunny, cold January day, marching in community parades, attending local programs and dancing at inaugural balls.

"Utah is as happy as a boy with a new pair of red-topped boots,” wrote an Eastern correspondent. "Everything and everybody, even to the babies, smiled and rejoiced,” wrote a Snowville reporter.

Statehood Day

From California to Polynesia

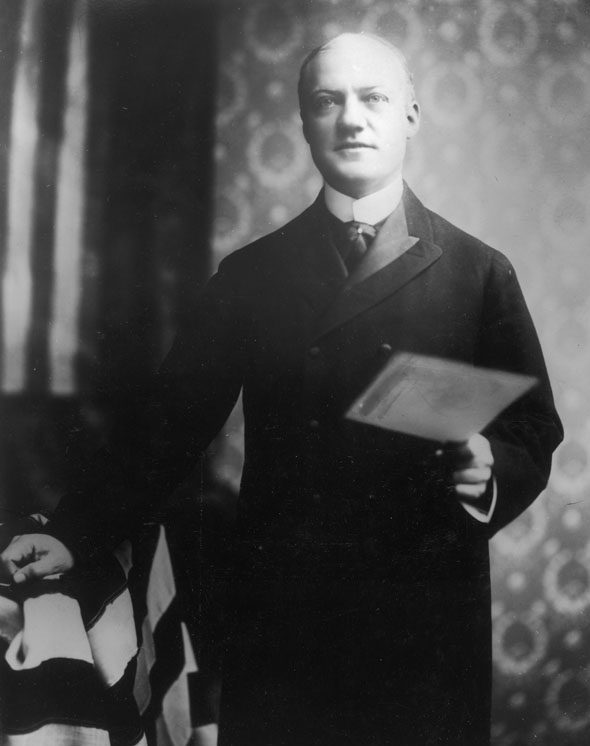

At the Inauguration ceremony at the Salt Lake Tabernacle, Wells, the then-36-year-old governor, offered a carefully considered address, calling upon residents and the state’s newly installed lawmakers to overcome complicated religious and political differences. One critic wasn’t especially impressed by the conciliatory tone of the speech, calling it “too extremely long” and “enough for four addresses.”

Significantly, the governor acknowledged one right anchored in the state’s constitution — that Utah had granted suffrage to its female citizens. Wells congratulated women “on their entrance into the full enjoyment of civil and political rights.” One program highlight came when Wells was presented with the pen President Cleveland used to sign the statehood proclamation.

“Though we have seen some interesting days in Utah, We have Never seen such a Day as this" is how Wilford Woodruff, president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, described statehood celebrations in a letter to his son.

Governor Heber Wells holding the inaugural address.

Credit: Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society

Across the State with Utah Style

On Statehood Day, towns across the state hosted parades and balls, as well as programs featuring local talent (such as in Ephraim, where prominent Utah artist C. C. A. Christensen recited an original poem), and many choral renditions of Stephen Evans’ newly written song, “Utah, We Love Thee,” which became the state song and is still the state’s designated hymn.

Many towns, such as Fairview and Parowan, feted older settlers with cheers, while many local programs acknowledged female voting rights. In Newton, three cheers were offered for “the Ladies,” while in Parowan, the Woman’s Temperance Association passed out yellow ribbons. In Huntsville, women opened their new brick two-story Relief Society hall, then marked the celebration of statehood and suffrage by serving dinner.

At the railroad station in Coalville, residents cranked up a massive, loud steam engine. In Corinne, the courthouse bell was rung with such spirit the $200 gong cracked. In Beaver, groups such as the Woman’s Suffrage Association and Latter-day Saints’ Relief Society competed to decorate vehicles, as did church youth organizations and Sunday School groups.

Manti hosted a sunrise service in the town square, “with anvils and dynamiters at the center, cannoneers on the right, musketeers on the left, shotgunners in the front,” encircled by people ringing cow and sheep bells. A town parade featured a man riding a burro dressed as Uncle Sam, followed by a squad carrying a banner: "Utah! One more strong arm for Uncle Sam.”

In Park City, when officials didn’t plan an event, 150 youth formed their own parade and marched through town serenading residents and local businesses.

In Kamas, men competed in ball games while children were offered sleigh rides accompanied by the Kamas Brass band. “Everybody and their cousin” turned out for the Clarkston program, which featured speeches, a comic song, a talk in German, and uniquely, a performance where male dancers invented forty-five new steps.

Women led parades in Coalville and Brigham City, which also featured a contingent of forty-five women, representing each state in the union. In the Nephi parade, one horse-pulled sleigh featured 27 women representing each of the then-established counties. High spirits and firearms led to injuries, such as the Brigham City resident who was accidentally shot in the back during a parade, and a young man in Fairview who suffered a facial wound, but returned to festivities after receiving stitches. In Fillmore, the town’s Liberty Hall was the site of a festive ball, but the building burned to the ground afterwards, the flames thought to have been caused by an exploding lamp.