Residents of Iosepa celebrate Pioneer Day (July 14) in 1913.

Credit: Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society

Iosepa

The Experiences of Religious Immigrants

Many immigrants to Utah in the late 19th century were drawn to the area by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Their experiences varied depending on who they were, where they came from, and what lifestyles and occupations they pursued in Utah.

Missionary Work in Hawai'i

Religious and Cultural Change

Beginning in the 1850s, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints established a mission in Hawai’i. The experience of the Hawaiian converts was complex, and a lack of firsthand accounts makes it difficult to determine how and why many of them came to embrace their new religion.

In the 1820s through the ‘Ai Noa, King Kamehameha II had done away with the traditional religion, leaving a void that was filled by Christian missionaries. The spiritual community offered by Latter-day Saint missionaries would have been one motivating aspect for the converts. Socially, the choice to convert would have been difficult. Many of the Hawaiians made the momentous decision to leave their families when they converted and moved to newly established church co-ops, but these co-ops also included economic advantages. Overall, conversion was a momentous decision that included the eventual goal of moving to Utah.

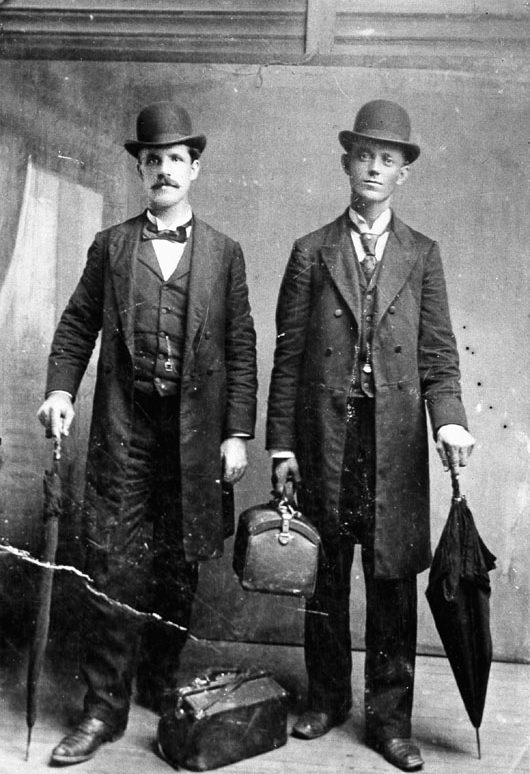

Latter-day Saint missionaries were sent all over the world to proselytize, this pair in Mississippi. A. T. Rose and G. M. Fryer, pictured here, are wearing Prince Albert coats and derbies with umbrellas and satchels, considered standard missionary attire. Credit: Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society

The simple forms hearken back to the ocean. The grid billows and shrinks becoming broken nets or open windows. The unexposed dark layers seep through the bright stripes, illuminating perimeters and resulting in anticipation and wonder.

Credit: “Polarities #8” by Jonathan Frioux. Courtesy of the Utah Division of Arts & Museums. All Rights Reserved.

The Move to Utah

The Hawaiian government restricted emigration from the islands, which complicated the move to Utah. Starting in 1873, a few Hawaiian Latter-day Saints would accompany missionaries on their return trips to Utah, and these immigrants began forming a community in the Warm Springs district of Salt Lake City. After the 1887 Bayonet Convention removed the restrictions, immigration from Hawai'i to Utah swelled.

Stereotypes and Citizenship

The Reality of Life in Salt Lake City

In Salt Lake City, the Hawaiian community, which was joined by immigrants from elsewhere in Polynesia, faced harsh discrimination. For years, newspapers and public discourse had disparaged their customs from several perspectives, and in Utah, they experienced these stereotypes even more directly. They also faced a lack of employment options, and several families petitioned for funding from the Hawaiian government to return home.

Deciding to Form a New Colony

Leadership in the church decided to create a colony for the Hawaiian and Polynesian community outside of Salt Lake City. They formed a committee made up of white Latter-day Saints Harvey H. Cluff, William W. Cluff, and Frederick A. Mitchell assisted by Hawaiian Latter-day Saints G. W. Kamakaniau, J. W. Kauleinamoku, and Napeha. After exploring seven potential sites, only one was found to be a suitable option: Skull Valley. The valley, which had previously been used for livestock grazing, was an isolated, arid area with temperatures that varied widely from summer to winter. However, its advantages outweighed its disadvantages, and so for $35,000, the Church agreed to purchase the ranch of John T. Rich. To avoid legal complications, it formed a company, the Iosepa Agriculture and Stock Company (IASC), to buy and manage the property.

Iosepa

A New Community

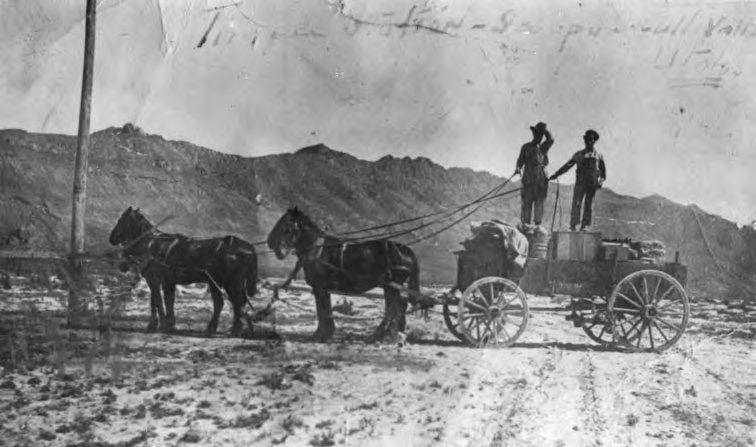

Some two-thirds of the Salt Lake City Hawaiian community moved to Skull Valley in the late summer of 1889. Volunteers summoned by the Church helped transport forty-six Hawaiians and their possessions to Iosepa, arriving on August 28. The rest either followed or emigrated to their homeland.

Although it shared many characteristics with other Latter-day Saint settlements in Utah, Iosepa was treated differently by the church. European settlers were left to adapt to the environment themselves, but Hawaiian settlers were overseen by white Latter-day Saint leaders. Much like the communities in Hawai’i, Iosepa was formed as a co-op. The community was headed by H. H. Cluff, who was fluent in Hawaiian and also headed the IASC. Although settlers held private livestock and lived in separate homes, they were all employed by the IASC and their wages were only usable at the general store.

The division of the land at Iosepa was based on Joseph Smith’s original plan for the City of Zion and included wide avenues and public spaces. A public square was placed in the center of town, and the plans included common buildings such as a schoolhouse. The 1,920 acres of land was equipped with 129 horses and 335 cattle as well as several buildings and access to multiple water sources. The church also bought a nearby sawmill, which provided building material for the houses, which were constructed on land distributed by drawing lots, starting on September 9, 1889.

The End of the Community

The Abrupt Abandonment of Iosepa

Iosepa flourished. Its agricultural output and land ownership grew, and the community eventually welcomed a phone line and a nearby train station, both of which helped reduce its isolation.

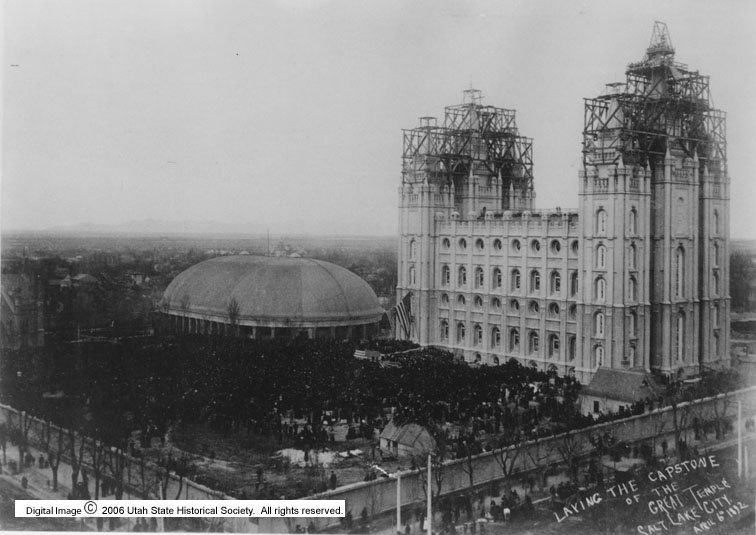

The end of the community was signaled in 1915 when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints announced plans to build a temple in Hawai’i. Many of the Iosepa residents had helped construct the Salt Lake Temple and were also able to assist in temple ceremonies, so they were interested in returning to Hawai’i to assist with the new temple. They were also interested in returning in order to involve their ancestors in temple ceremonies and, possibly, to escape the harsh landscape and associated health issues brought about by life in Skull Valley. The church offered to pay their fares, further encouraging the move, and eventually many of them left. Iosepa was abandoned in 1917 and sold to another Latter-day Saint company, the Deseret Livestock Company.

Legacy of Iosepa

The Iosepa Historical Society, which was formed in 1985, is the contemporary voice of the Iosepa settlement, which is commemorated every Memorial Day. The influence of Hawaiians and the wider Polynesian community is still felt in the state. There are more people of Polynesian descent in Utah than in any other state in the contiguous United States.