One hundred and twenty-five years ago this year, Utah became the forty-fifth state to enter the Union, ending a long, painful struggle to be so recognized. As state officials ask the public to celebrate the anniversary, the moment is ripe for historians to reflect on the statehood experience. At this commemorative juncture, how might you distill in a few spoken minutes the meaning of statehood? This deliberately open-ended question is designed to prompt broad and diverse reflections of Utah as a geographical place, political entity, and/or cultural community.

As a public historian I am interested not only in what happened in the past, but about how the public remembers and crafts the past to fit the needs of a particular present or moment in time. The anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote,

“We are never as steeped in history as when we pretend not to be, but if we stop pretending we may gain in understanding what we lose in false innocence.”1

Anniversaries like statehood are to be celebrated, but something more is required if the true authenticity of the event and the “false innocence” of the present is to be addressed. In this sense authentic commemoration expresses a relationship between what we know about the past and our duties to our present moment. 2

Utah’s bid for statehood coincided with U.S. efforts at nation state building during the second half of the nineteenth century, the aftermath of the Civil War, and the decimation and removal of Native American tribes across the West. In this context, Latter-day Saint church leaders sought statehood as a path to political and social independence. Free of obnoxious federal appointees, they could bring about the Kingdom of God on the earth, a presumably benevolent theocracy very much at odds with the day’s liberal republican values. As the historian Steven Hahn explains, following the Civil War, sectionalism gave way to projects of national unification. Under this program, the new nation would be one of free labor and free markets headed by a strongly centralized federal government.3 In the case of Utah’s bid for statehood, the federal government demanded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints renounce polygamy, launching the church on a path of sweeping assimilation and painful change familiar to historians of Mormonism and Utah history. A high price to pay for political self-determination.4

Over time, the meaning of statehood came to reflect the Church’s own efforts at Americanization.

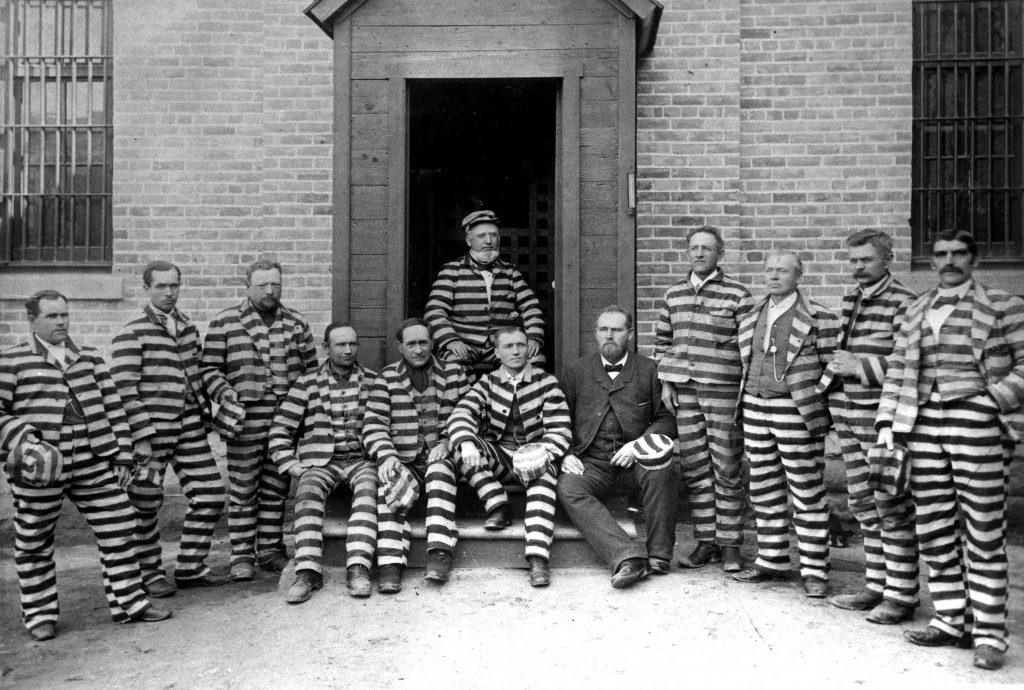

Over time, the meaning of statehood came to reflect the Church’s own efforts at Americanization. In 1947, centennial organizers spun the Mormon pioneer arrival to Utah as the American story writ large.5 In a sense, This is the Place Monument became the West’s Plymouth Rock. Indeed, for most of the twentieth century, the history of Utah’s territorial period has been that of the Mormon pioneer story—and with good reason. Yet in the intervening time, we have lost sight of others’ histories and what statehood meant to these people—individuals who came to Utah who were not Mormon pioneers and of course the Native peoples for whom statehood meant final removal from their lands. Focusing on and learning these histories does not diminish the history with which many of us are familiar and continue to study. They do, however, offer new ways of understanding that past and force us to confront our own false innocence, especially when what we learn reveals an uncomfortable or even difficult past. To ignore these histories is to be false to the actual narrative many of us know and celebrate: that of a religious minority who sought refuge far from the reach of destructive mobs and an unresponsive government. Suddenly what was once a black and white film bursts on our screen in vibrant color, whether we like the picture that emerges or not.

Suddenly what was once a black and white film bursts on our screen in vibrant color, whether we like the picture that emerges or not.

And what should our response be when that past makes glaringly obvious the gulfs in moral sensibilities and attitudes between our time and those of previous generations? As Trouillot expresses, a misplaced sense of collective guilt “often diverts us from the present injustices for which previous generations only set the foundations.” He continues, “What we know about slavery or about colonialism can—should, indeed—increase our ardor in the struggles against discrimination and oppression across racial and national boundaries. No amount of historical research about the Holocaust and no amount of guilt about Germany’s past can serve as a substitute for marching in the streets against German skinheads today.”6

As we celebrate statehood and ponder its many meanings, what are the needs of our present time and how can these celebrations remain authentic? Returning to Trouillot:

“Only in the present can we be true or false to the past we choose to acknowledge.”7

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), xix.

- Trouillot, 148, 150.

- Stephen Hahn, A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830-1910 (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), 268-69.

- See Thomas Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of Latter-day Saints, 1890-1930 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1986).

- “Auto Caravan to Retrace Brigham Young’s Journey,” Milwaukee Journal Green Street, January 7, 1947, reel 4, Newspaper Clippings, Series 11963, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Trouillot, 150.

- Trouillot, 151.