One hundred and twenty-five years ago this year, Utah became the forty-fifth state to enter the Union, ending a long, painful struggle to be so recognized. As state officials ask the public to celebrate the anniversary, the moment is ripe for historians to reflect on the statehood experience. At this commemorative juncture, how might you distill in a few spoken minutes the meaning of statehood? This deliberately open-ended question is designed to prompt broad and diverse reflections of Utah as a geographical place, political entity, and/or cultural community.

Statehood expanded Utahns’ opportunities for self-government, including the right to elect major officers in the executive branch: the governor, secretary of state, auditor, treasurer, and attorney general. Conversely, in the territorial era major territorial officers were appointed by the president with the consent of the US Senate. Lawmakers had functioned in a popularly elected territorial legislature, but the US Congress possessed absolute veto power over any laws enacted. By contrast, laws passed by Utah’s state legislature were exempt from congressional review and veto. In place of the territorial judicial system, which was staffed by federal appointees, the Utah Constitution established state district courts and a state supreme court; until 1945 the judges in these courts were popularly elected. During the territorial era, Utahns along with the residents of other territories, were barred from voting in presidential elections. Statehood conferred the privilege of voting in presidential elections, along with representation in the Electoral College. Statehood also entitled Utahns to participate in the process of amending the US Constitution. The Utah Territory had been represented in the House of Representatives by an elected, non-voting territorial delegate but as a state Utah acquired full representation and voting rights in the House and Senate. Statehood with a new state constitution also restored voting rights to the territory’s women, whose electoral rights had been revoked by Congress.

Statehood expanded Utahns’ opportunities for self-government, including the right to elect major officers in the executive branch: the governor, secretary of state, auditor, treasurer, and attorney general.

When it was admitted to the Union, Utah received title to three sections of public land in each township—tracts totaling 7.4 million acres. Originally managed by a State Land Board, over half of the lands were sold to generate revenue for the state. The remaining state trust lands, totaling 3.4 million acres, continue to generate revenue. Leases and royalties from those lands have provided nearly $2 billion for the state since 1994.

Statehood also created new fiscal obligations for Utahns, including the operation of state offices, courts, and institutions such as the prison and a school for the blind. Formerly these institutions had been partly subsidized by the federal government. The new state legislature increased taxes and floated bonds to cover the new expenses. With the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, Utahns also became susceptible to a federal income tax, a tax that was not imposed in territories.

The federal government’s investment in Utah’s economy expanded enormously in the first fifty years of statehood. Government policy and investment had significantly influenced Utah’s economy in the territorial era, beginning with the construction of Camp Floyd in 1858 and extending to the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. But the government’s investments in the territorial era were modest compared to what occurred between statehood and World War II. Federal largesse early in the twentieth century included expensive, sophisticated water systems engineered by the Reclamation Service and its successor, the Bureau of Reclamation. In the 1910s, Congress began to heavily subsidize highway construction.

The financial benefits of statehood became especially evident during the Great Depression. Territories received little of the federal largesse associated with the New Deal. With a total federal investment of $289,301,781 between 1933 and 1939, Utah ranked ninth among the states in per capita expenditures by the federal government during the Depression. The benefits were immense, including close to 300 new public buildings as well as improved roads and new reservoirs, water and sewer lines, and recreational facilities. By 1940, thanks to extraordinarily heavy federal spending in the state, Utah’s unemployment rate, which had greatly exceeded the national average in 1932, had fallen to two-thirds of the national rate.

Then, during World War II, unprecedented levels of investment created a mammoth steel plant in Utah Valley, a small arms factory that temporarily became Salt Lake County’s leading employer, ten defense installations, and a military hospital. Territories were eligible to host wartime installations, but the likelihood of securing such facilities was increased by the presence of popularly elected, politically influential senators and representatives on Capitol Hill.

The federal government’s investment in Utah’s economy expanded enormously in the first fifty years of statehood.

The presence of state senators and representatives in Washington, DC, serving on powerful committees, who advocated for federal investment in the state, continued to benefit Utahns following World War II. Defense contracts, the continued operation of military bases including Hill Air Force Base which has in many years been the largest employer in the state, and expensive water projects including the construction of Flaming Gorge and Glen Canyon Dams and the completion of the Central Utah Project have come to Utah through the lobbying and logrolling of senators and representatives. Advocacy for the state in Congress by Utah’s representatives was also crucial in securing funds for infrastructural improvements including federal highways and airports and social services. In FY 2019, over nearly one-fourth of the state’s budget was supplied by the federal government.

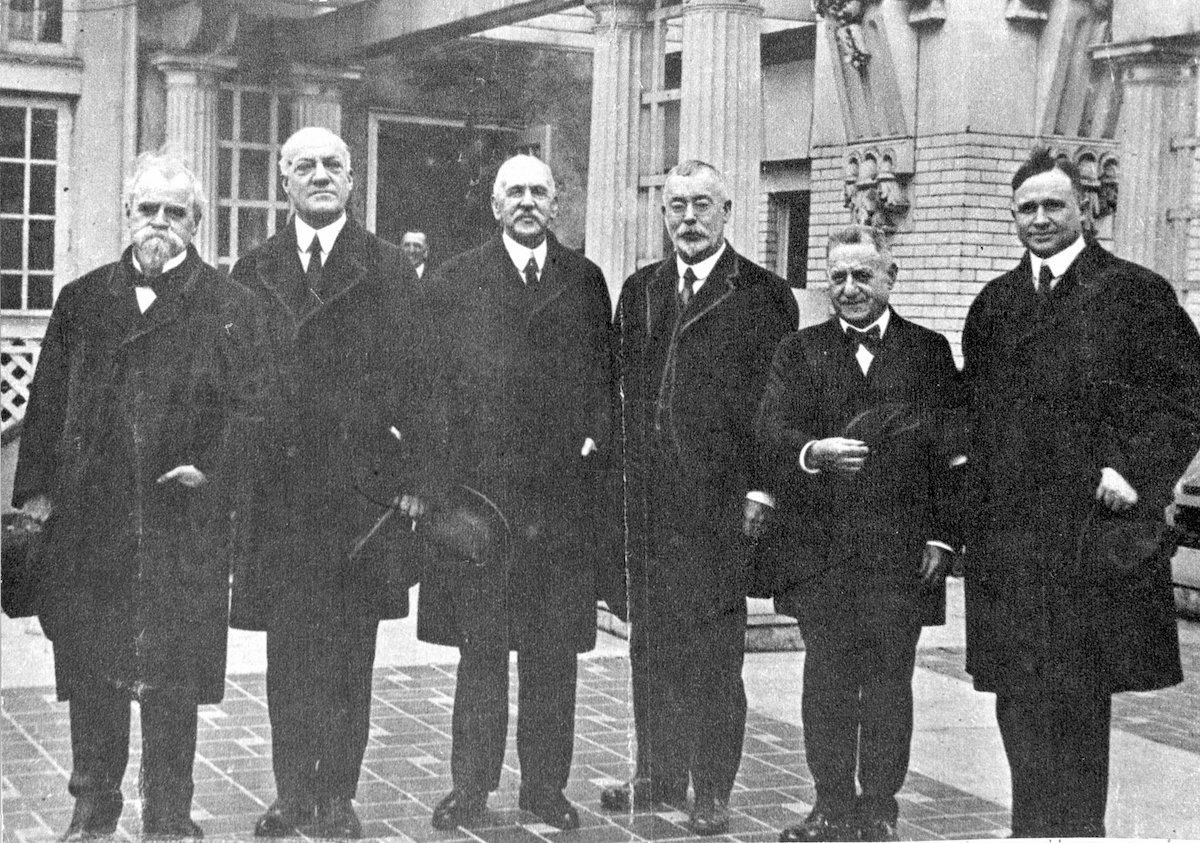

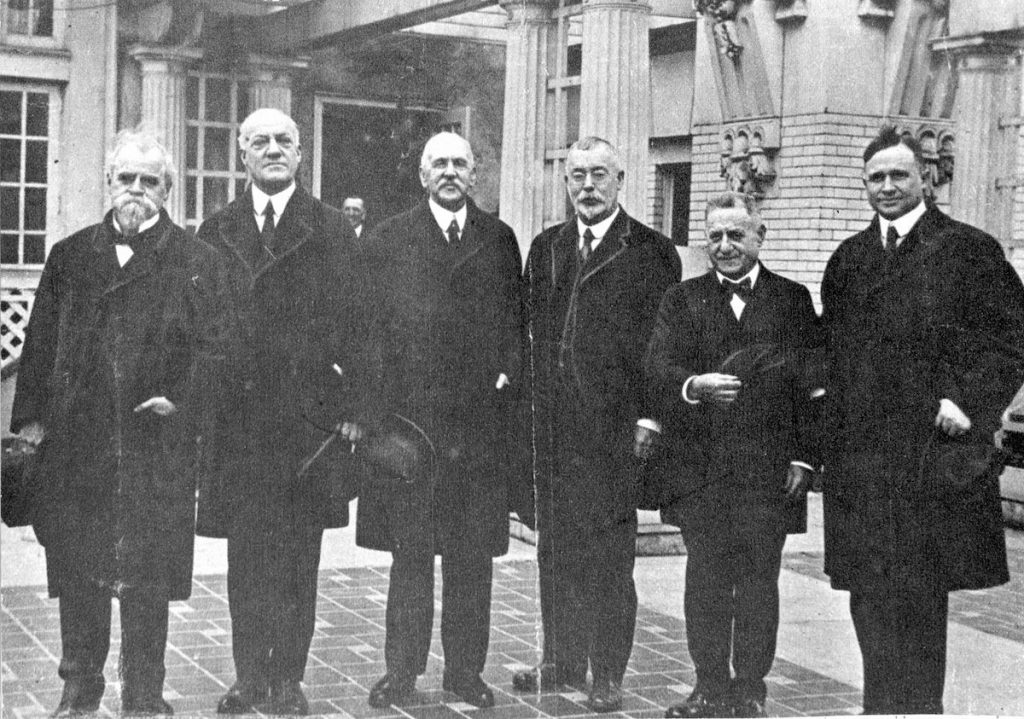

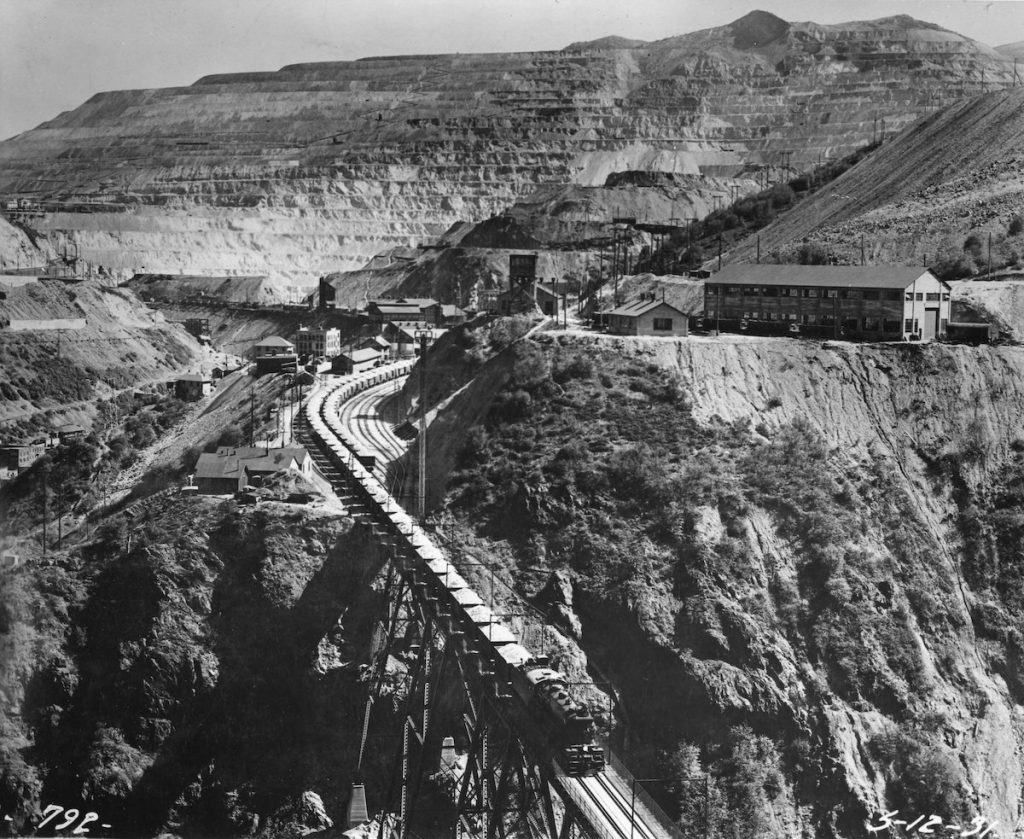

Statehood also resulted in a fuller incorporation of its residents and economy within the nation. This took many forms, including military service in the nation’s wars, defense contracts, and the state’s consequent complicity in the nation’s geopolitical strategy. The contrast between the Utahns’ marked avoidance of the Civil War and their patriotic enlistment in the Spanish-American War shortly after statehood reflected the surge in patriotic identification with the nation that accompanied statehood. In contrast to Brigham Young’s vision of an economically self-sufficient, isolationist economy, the state’s economy became increasingly integrated within the nation’s urban-industrial economy. Statehood did not mark a magic fault line in the state’s economic evolution, but it accelerated developing economic trends by placing Utah on an equal footing with the rest of the nation. Utah’s economic nationalism was especially evident in her key economic sectors: mining and agriculture. In the decades immediately following statehood capitalist investment and the adoption of new technologies from outside the state gave rise to the Utah’s premier mining industry—copper. Expensive, speculative private reclamation projects in places such as the Bear River Valley and Delta that attracted settlers from across the nation; a network of agricultural experiment stations and farms; and new opportunities to sell farm products including milk, wheat, sugar beets, and tomatoes to corporate processing plants tied Utah farmers to national markets and market trends.

In contrast to Brigham Young’s vision of an economically self-sufficient, isolationist economy, the state’s economy became increasingly integrated within the nation’s urban-industrial economy.

Culturally the state’s residents also evolved. Palpable divisions, many of them religiously based, persisted, but statehood at least necessitated a tentative broadening of sympathies and a tamping down of tensions. Utahns abandoned their distinctive, religiously based Liberal and People’s parties, joined national political parties, and banned polygamy in their state constitution. Disappointed in their hope to retain by subterfuge their sacrament of plural marriage well into the twentieth century, Latter-day Saints bowed to political exigencies in response to embarrassing congressional investigations following Reed Smoot’s election, preferring representation on Capitol Hill to the opprobrium of continued defiance of American cultural norms. After the church began excommunicating polygamists, it became easier for Utahns to forge political alliances that crossed religious divides, such as the alliance of evangelical protestants and some Mormons in support of statewide prohibition and the alliance of commercial leaders across religious lines to suppress silent films that maligned Utah. The state’s popular election of the Simon Bamberger in 1916, the nation’s third elected Jewish governor, demonstrated the extent to which accommodation of religious and cultural differences in the political arena was possible.