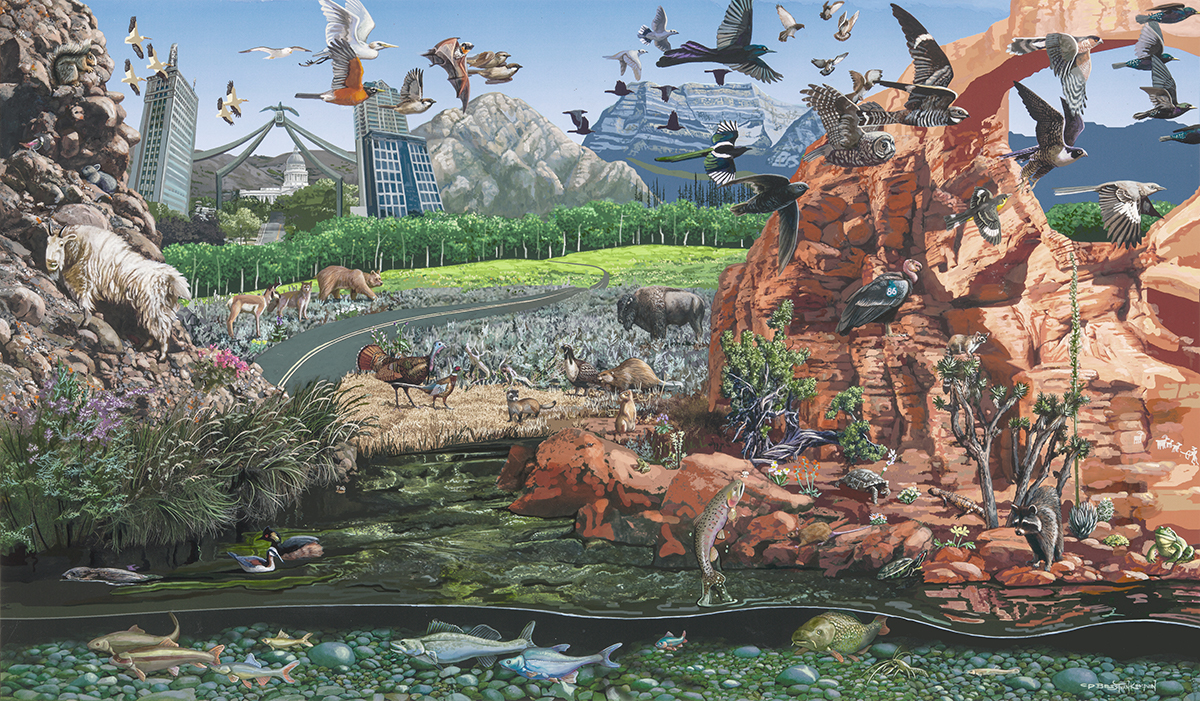

ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF UTAH ECOLOGY

Carel Brest van Kempen

Since its admission to the union in 1896, Utah has seen many changes, not the least of which are the remarkable transformations to its diverse ecology. With nearly 85,000 square miles of land ranging in elevation from the 13,500 foot King’s Peak in the Uinta Mountains to Washington County’s Beaver Dam Wash at 2,000 feet, our state enjoys a wide assortment of habitats that host a rich assortment of animals and plants. This painting illustrates some of the changes those systems have seen over the past 125 years: changes that have been driven by water diversion, invasive species, livestock, agriculture and urban development, as well as the simple fact that ecosystems are dynamic things that are always changing.

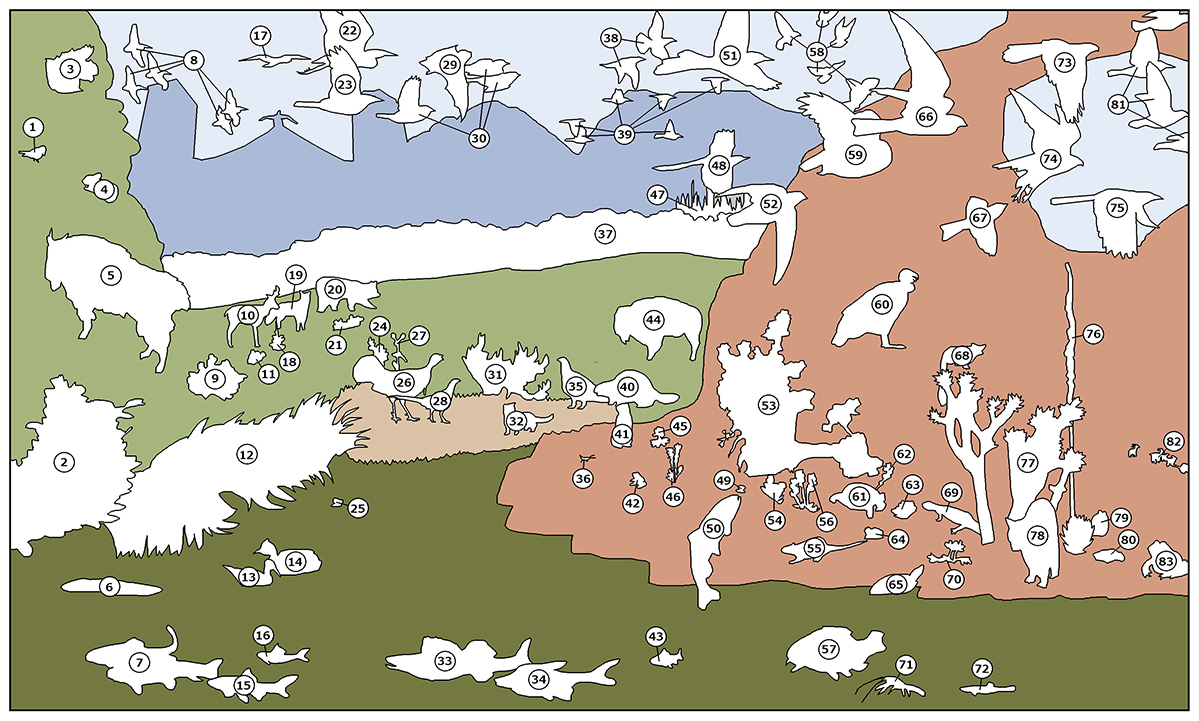

Utah’s animals and plants have always been of central importance to her people, as evidenced by the 9,000-year-old Bighorn Sheep petroglyphs in the “Great Hunt” panel in 9-Mile Canyon (82). The first Utah wildlife species commercially exploited by European-Americans were the American Beaver (40) and the American Bison (44). Numbers of the former species have fluctuated wildly over the past 125 years, but it has persisted, where the latter one was probably completely eliminated from Utah by the time the first Mormon settlers arrived in 1847. Bison were reintroduced to Antelope Island around the time of statehood, and into the Henry Mountains beginning in 1941.

As an arid state, water is essential to all life in Utah, and the redistribution of this invaluable resource has been a major driver of ecological change. Even minor diversions of water can have unpredictable results. Late in the 20th Century, guzzlers were installed in the West Desert to try to increase habitat for Bighorn Sheep. That additional water allowed Coyotes to move into the area and wipe out the local population of Kit Foxes. For much of the state, the Great Salt Lake serves as the ultimate repository for water. Its saline content and surrounding salt flats seem inhospitable, but the lake is an essential part of the state’s ecology. Not only does it affect weather patterns over the lands surrounding it, it’s a significant staging area for many migrating birds, including half a million Wilson’s Phalaropes (13) and most of North America’s Eared Grebes (14), as many as 5 million birds, that stop to fatten up on brine shrimp before migrating on to Mexico. The Great Salt Lake hosts many nesting birds, including one of the world’s biggest colonies of American White Pelicans (8) on Gunnison Island. Since the lake is too salty for fish to survive, the adult pelicans must commute twice daily to fish for their growing young. In 1896, Utah Lake was the appointed fishery, but man-made lakes in Salt Lake Valley have since created closer fishing holes, and in the 21st Century, many pelicans provision their nestlings with fish caught in urban settings. Thanks to light pollution, the once strictly diurnal birds can also fish and fly by night. The lake is also home to large nesting populations of California Gulls (17), Utah’s state bird, eulogized for the role they were said to play in saving Mormon settlers’ crops from a swarm of Mormon Crickets (36) in 1848. The life in Utah’s rivers has changed immensely since 1896. In many cases, the water itself is different, most notably in the Jordan River, which is much warmer now, due to diversion of cold mountain streams that flow into it and to a warming climate. It’s also richer today in nitrogen and phosphorus from agricultural runoff and other sources. Changes in freshwater invertebrate fauna are poorly understood, although some species have been well studied, including the Fish Springs Marsh Snail, which appears to have recently gone extinct, and the invasive Zebra and Quagga Mussels, which have given wildlife managers heartburn, trying to stop their spread. Three species of introduced crayfish, including the Northern Crayfish (71) have significantly impacted the ecology of many Utah waters. Many of our fish species are newcomers introduced in the last 125 years, either intentionally as game fish or inadvertently. The Cutthroat Trout (50) and three whitefish species endemic to Bear Lake are native. All our other sportfish, like the Walleye (33) have been introduced, as have the Asian Common Carp (57), which is plentiful in slow-moving waters throughout the state. Another pernicious introduced species is the fecund little Red Shiner (43), which has been a fierce competitor in the Colorado and Virgin Rivers. A very recent arrival is the Weather Loach (72), a common aquarium fish that is now plentiful in the Jordan River Drainage and some estuaries surrounding the Great Salt Lake, and is becoming an important food for kingfishers and some other native wildlife. Many of Utah’s native fishes are imperiled today, including the June Sucker (7), native to Utah Lake and the Provo River (endangered), Bonytail Chub (15) of the Colorado River (critically endangered), the Woundfin (16), found throughout the Colorado and Gila drainages in 1896, but restricted today to the Virgin River (critically endangered), and the Humpback Chub (34) of the Colorado, White and Green Rivers (endangered). Utah’s waterways look different today from above the surface as well. Many of them are lined with invasive plants like Saltcedar (2) and/or Phragmites (12), a showy grass.

Another important invasive grass is Cheatgrass, which has taken over large portions of the state since 1896, particularly in areas with a history of overgrazing. When this grass goes to seed in early summer, the above-ground part dies, leaving large areas devoid of forage for many insects and herbivorous vertebrates. Much of the land now covered in Cheatgrass was originally the province of vast stretches of Big Sagebrush (31) grasslands, typical of the Great Basin bioregion. At higher elevation, these sagebrush steppes gave way to woodlands of Pinyon Pine and juniper: Utah Juniper (53) in southern Utah, Rocky Mountain Juniper further north. Many fragments of Utah’s original sage steppes remain today, but they’re an impoverished version of their original selves. At the time of statehood, great flocks of the two species of sage grouse, indicators of healthy sage habitat, strutted over much of Utah. Today, only a few small populations remain in the state, and the smaller species, the Gunnison Sage Grouse (35), is considered endangered.

Another imperiled Utah ecosystem is the little extension of Mojave Desert in the southwestern corner of Washington County. Its primary threat is from the booming city of St. George and diversion of water. This little corner of Utah is home to many plants and animals normally only found further south. These include the stately Joshua Tree (77), a large yucca named by Mormon settlers who compared its silhouette to the prophet Joshua with arms held aloft, and the Utah Agave (76), the northernmost species of a mostly Mexican genus. Among the subtropical members of the animal kingdom present in Washington County are the Gila Monster (69) and the Mojave Desert Tortoise (61), the latter of which was the sole turtle species present in Utah at the time of statehood. Early in the 20th Century, A broken dike accidentally released captive Spiny Softshell Turtles into the Gila River. From there, they dispersed up the Colorado River and the Virgin River into Utah. The Western Painted Turtle and Red-eared Slider (65) have been introduced into numerous locations about the state. Recently a fifth species, the Common Snapping Turtle, appears to be established in the Provo River. Another cold-blooded member of the Washington County fauna, the Relict Leopard Frog (42), occurred throughout the Virgin River Drainage and possibly beyond in 1896, but it appears to have gone extinct in Utah in middle of the 20th Century. A couple of small populations of the species are known to remain in Nevada’s Moapa Drainage. Just what hit these frogs so hard is difficult to say. Surely the capping of springs and diversion of water played a part, along with the introduction of predatory crayfish and the American Bullfrog (83) in some areas, but it seems there must be more to the story. Frogs have seen significant global declines since 1990, largely because of the spread of the fungal disease Chytridiomycosis. Some of Utah’s 14 native species of tailless amphibians have been affected, particularly the Columbia Spotted Frog and Boreal Toad, but there are still healthy populations of other species, and Western Chorus Frogs and Great Basin Spadefoots even persist in parts of the highly urbanized Salt Lake Valley.

Paved Roads have significant effects on ecosystems. They serve as corridors for inadvertent delivery of seeds from distant areas on vehicles. Roadsides form little microhabitats quite different from the surrounding area. Building the road breaks up the soil and changes its composition. The pavement diverts rainwater to the edges, increasing the moisture delivered there. Roadsides are always fine places to look for invasive plants. A few more of Utah’s important invasive plants include Hoary Cress (21), which is toxic to livestock, but provides forage for some native wildlife. It is probably an important factor in turning the Cabbage White (49) into one of Utah’s commonest butterflies, as well as assisting the impressive increase in Lesser Goldfinches (67) in the north half of Utah in the 21st Century. Houndstongue (18) is well-known today, not so much for its pretty violet flowers, but for the teardrop-shaped burrs they give rise to. Myrtle Spurge (11) is one of the more invasive roadside species. Rounding out our list is the Camelthorn (24), a Eurasian invasive that is the bane of alfalfa farmers, and the familiar Scotch Thistle (27). Many of Utah’s rarest plants are restricted to small geographic areas. A few examples (along with their conservation status and range) are the Kodachrome Bladderpod (80) critically imperiled, Kane County; Wright’s Fishhook Cactus (79) imperiled, Emery, Sevier, Wayne and Garfield Counties; Fall Buttercup (70) critically imperiled, Garfield County; Barneby’s Pepperweed (63) critically imperiled, Duchesne County; San Rafael Cactus (64) imperiled, Emery County; Gierisch’s Globemallow (56) critically imperiled, Washington County and adjacent Mohave County, AZ; Dwarf Bearclaw Poppy (54) critically imperiled, Washington County; Shivwitz Milkvetch (46) critically imperiled, Washington County; and the Clay Phacelia (45) critically imperiled, Utah County. Utah is a center of diversity for the beautiful penstemons, with more species (over 100) than any other state. Utah’s penstemon species include 18 listed as vulnerable, 14 imperiled and 5 critically imperiled, including the Navajo Penstemon (62), found only in the San Juan County portion of the Navajo Nation, and the Lime Penstemon (9), which grows on east-facing limestone in a small area where Utah, Nevada and Arizona meet.

The causes of the Relict Leopard Frog’s extinction in Utah are mysterious, but a few wildlife species were eliminated intentionally. Well before statehood, many species began being persecuted for interfering with agriculture and livestock interests. In 1896, nearly half of Utah’s area was home to three species of Prairie Dog (and Black-tailed Prairie Dogs may have extended into eastern Utah in those days). Ranchers killed them, seeing them as competitors with their livestock and their burrows as potential hazards to them. The Prairie Dogs couldn’t compete anyway, and grazing as it was done in the early 20th Century left little behind for the rodents. Those three prairie dog species survived the onslaught, but occur today in far smaller numbers over a far smaller area. The Utah Prairie Dog (41), Utah’s only endemic mammal species, is listed as critically endangered. Black-footed Ferrets (32), dependent on large Prairie Dog towns, occurred through the eastern fifth of Utah 125 years ago. The species was extirpated from the state by the mid-1900s. Black-footed Ferrets were feared extinct until a small colony was found in Wyoming around 1980, and the last 18 individuals were taken into a captive breeding project. During the past two decades, captive-bred Black-footed Ferrets have been reintroduced into White-tailed Prairie Dog towns in eastern Utah.

Large predators were also subjected to campaigns of intense persecution in Utah, becoming systematic around 1910. Within 20 years, the Brown Bear (20) had been eliminated from the state. The Gray Wolf (19) was exterminated soon after. Brown Bears have never returned, but a few wolves descended from reintroductions in Wyoming and Idaho have entered the state in recent years. Such sightings can be expected to increase in the future. Mountain Lions and Black Bears were severely reduced, but never completely eliminated from Utah. With the diminishment of these large predators, populations of Mule Deer skyrocketed across the state. Clearing of sections of forests also increased the amount of forest edge in the state, the habitat the deer exploit. It is believed that no Moose existed in Utah in 1896, but soon after that, they began to expand naturally into the northeast part of the state, mostly in the Uintas. In the 1970s, wildlife officials began planting Moose in Utah, and by the end of the century the species was close to carrying capacity in much of the northern third of the state. In recent years, White-tailed Deer have also naturally expanded into Utah from Idaho and Wyoming. In 1962, Mountain Goats (5), which were not native to Utah, were transplanted to the Wasatch Front, where they’ve continued to thrive. Animals from that population have also been introduced into the Uintas. In 1972, Bighorn Sheep, which had died out in the Wasatch Mountains, probably from diseases introduced by livestock, were transplanted, but that experiment was a failure. Of Utah’s ten species of hoofed mammals, only the Pronghorn (10), the most ancient of them all, has decreased in numbers since 1896.

Like the Black-footed Ferret, the Peregrine Falcon (74) experienced a crash in the 20th Century followed by a Human-managed recovery. After World War II, agricultural use of DDT virtually halted reproduction of several bird species across the US, including the Peregrine. A 1972 ban on the pesticide and a rigorous captive-breeding and reintroduction program have restored the falcon to healthy numbers in our region. The wide-ranging California Condor (60) probably used to visit Utah occasionally (there is a record from the Beaver area from 1872) but it had not nested here for thousands of years. Once the total population of the species dropped to 22 birds in the mid-‘80s, the decision was made to trap them all and breed them in captivity for later release. The project succeeded beyond all expectations, and today there are over 500 California Condors, more than half of them living in the wild, including a nesting pair in Zions National Park.

A number of non-native birds have been introduced to Utah specifically for hunting. Of our 12 species of gallinaceous, or chicken-like bird species, fully half are introduced. California Quail were first brought into the Salt Lake Valley from the west coast in 1869, and Ring-necked Pheasants (28), native to Asia, starting around 1890. Gray Partridges and Chukar Partridges were introduced from Eurasia in 1911 for the former and for the latter in the 1950s and ‘60s. The White-tailed ptarmigans found today in the Uintas are descended from birds introduced in the 1970s. The story of the Wild Turkey (26) is harder to piece together. Ancestral Puebloan people in what is now southeastern Utah used blankets/robes made of turkey feathers some 7,000 years ago, but whether they came from local birds or were traded from other regions is unknown. At any rate, there’s no evidence that Wild Turkeys lived in Utah in the Nineteenth Century. They were first introduced here in 1952, and over the past 30 years they have become plentiful over much of the state.

As the Human population grew in Utah, the landscape was altered to feed and house them. Those changes made life more difficult for many native species like the uncommon Spotted Owl (59), but some others were quick to adapt. The American Robin (23) and the Black-billed magpie (48) were surely two of the first native animals to learn to thrive with the changes. Others were slower to adapt. American Crows (39) were probably absent from Utah at the time of statehood. During the 20th Century, a few small populations sprang up around the state in agricultural areas. Early in the 21st Century, though, crows suddenly burgeoned across the Salt Lake Valley, resulting in a very large population from Utah County up to Weber. Why this population explosion failed to happen until the 2000s is anybody’s guess, but it’s likely that once a community of crows was established, young birds looking for nesting territory became more likely to put down stakes. The Cooper’s Hawk (73) was likewise slow to adapt to urban life. Before the 1970s, it was unheard of for them to nest anywhere near Human habitation, but in the ‘80s, they began building nests in the suburbs of Salt Lake City. As more hawks grew up in suburban settings and felt comfortable there, the nests increased to the point where the Cooper’s Hawk is now our commonest suburban raptor. This was not a local phenomenon, either; Suburban nesting of Cooper’s Hawks became common around the same time in much of the country. It’s likely that large numbers of nutritious and easy-to-catch House Sparrows helped move this trend forward. In some species the trend is reversed. The Common Nighthawk (66) thrived in many Utah cities in the latter half of the 20th Century, but soon after 2000, their numbers plummeted. Among the possible factors contributing to their decline are the arrival of American Crows and the recent general decline of insects in North America. This second factor is poorly understood. Pesticides, monoculture farming and light pollution are probably involved, but the phenomenon needs a lot more study. There is evidence that a local butterfly, the Utah Common Wood Nymph (25) has been severely impacted by mosquito abatement programs. Probably related to the insect and nighthawk declines has been a general decline of bats in Utah, which is also very poorly understood. Utah is one of only 7 states where the deadly bat disease White Nose Syndrome has not been found. Representing this animal group in the illustration is the spectacular Hoary Bat (29), found in coniferous woods all over the state.

Some of our best-known introduced species are commensal on Humans, that is, they live in close association with us, surviving on food we inadvertently supply. The House Mouse and Norway Rat (55) were both introduced from Eurasia, and were well established here by the time of statehood. The House Sparrow (30) was probably established here around that time, and the Common Starling (81) around 1940. Rock Pigeons (58), originally native to Eurasia and North Africa, have been domesticated for thousands of years, and escapees have populated urban areas worldwide. They were introduced to North America in the 1600s, and were probably established in Utah before statehood. All of these animals, House Mouse, Norway Rat, sparrow, starling and pigeon live as commensals in Utah and do not live in wilderness areas. A couple of commensal species have settled In Utah very recently. Both the Eurasian Collared Dove (38) and the Fox Squirrel (3) got their footholds here in the 21st Century. The squirrels were probably transported here accidentally from the eastern US with cargo. Being capable of flight, birds are more efficient at dispersing themselves, should that be their disposition. Eurasian Collared Doves were accidentally introduced into the Bahamas in the 1970s and have spread across the continent in spectacular fashion since. Another bird species, the Great-tailed Grackle (51), has followed corridors of humanity north to us from Central America. It’s believed that the Aztecs introduced them into the Valley of Mexico in the 15th Century. Around 1900 they crossed into southern Texas, and by the late 1970s they reached St. George. It was only about 2020 that they firmly established themselves in Salt Lake City. The Northern Mockingbird (75) has also spread north in recent years, becoming increasingly common in the northern part of the state. The Cattle Egret (22) has made a similar journey. Wayward egrets blown across the ocean from Africa ended up in the Guianas of South America around 1900, and finding the newly-created habitat of cattle pastures to their liking, they started spreading throughout the Americas. They reached Florida by 1940 and were first noticed in Utah in 1963. By the 1980s they were commonly breeding in the state. Unlike the other commensal species mentioned, Cattle Egrets also flourish in wildlands. The Raccoon (78) is another “facultative commensal,” an animal that can live as a Human commensal or in the wild. Raccoons did not live in Utah until the 1950s or ‘60s, and came here through a combination of natural expansion and Human introduction. They seem to have lived in the wildlands before venturing into the cities. They are now common in much of the state and in some areas are displacing their native relative the Ringtail (68). Another introduced species is the South American Nutria (6), which was first imported to Utah to farm for pelts in the 1930s. When the fur farm went bankrupt, the animals were released. Nutria have become a problematic invasive species in much of North America, but here in Utah they have remained uncommon and innocuous…so far.

Climate change is a driver of ecological change that began very recently, so we’re only starting to see its effects. Probably the most conspicuous effect in Utah is the increase in bark beetles in parts of the state. More of these native insects survive the increasingly warm winters, and once their numbers reach a certain point, they can result in large die-offs of trees. In Utah, this has been most evident with Lodgepole die-offs from Mountain Pine Beetles in the Uintas and Spruce Beetles taking out Engelmann Spruce (47) in the Dixie and Manti-La Sal Forests. Climate change threatens other high-altitude trees like our new official state tree, the Aspen (37) as well as animals adapted to high-elevations like the American Pika (4), the Black Rosy-finch (1) and the poorly-understood American Black Swift (52), which already appears to have seen a 90% drop in total population since 1970.