One hundred and twenty-five years ago this year, Utah became the forty-fifth state to enter the Union, ending a long, painful struggle to be so recognized. As state officials ask the public to celebrate the anniversary, the moment is ripe for historians to reflect on the statehood experience. At this commemorative juncture, how might you distill in a few spoken minutes the meaning of statehood? This deliberately open-ended question is designed to prompt broad and diverse reflections of Utah as a geographical place, political entity, and/or cultural community.

I want to begin by admitting I’ve never been a fan of historical anniversaries, or at least I don’t spend much time thinking about the past in that context. Anniversaries tend to mark momentous events as static moments in time, suggesting a culmination rather than a continuation. And like all historic events (and history itself), anniversaries are celebrated in service to the needs of the present.

All that said, anniversaries do serve a purpose, and such celebrations are aspirational by nature. They help us think about how far we have come and who we want to be, as much as commemorating who we have been and are now. They help us to remember and seek, even as they help us to forget and ignore.

So, I started thinking about the significance and meaning of statehood in terms of remembering and forgetting, which led me to thinking about the meanings of statehood “for whom?”

The creation of one state is almost always the dissolution of another.

First, consider the axiom that the creation of one state is almost always the dissolution of another. We tend to forget that the people here before were forcibly dispossessed of their homelands in order to create the territory and state later named after them—the “Yutas”—Utes, as well as Goshutes, Paiutes, Shoshones, and Navajos. That removal—by violence, treaty, disease, and population collapse—created the public and private land Utah settlers reshaped as their own. Beyond those boundaries lay remnant homelands, reservations, treated as inconvenient islands that eventually would be broken up, allotted, and absorbed—that those original Utahns and their places would eventually disappear into the new state. With the end of federal treaties comes the end of nation-to-nation negotiations, and with the allotment of reservations the territorial dispossession of Utah’s Native peoples was nearly complete, right at the moment of their population nadir, right at the dawn of Utah’s statehood.

While Utah’s Native peoples did not disappear, the interests of the new state did little to help. Excluded from citizenship until the 1920s, denied federal self-determination until the 1930s, facing state-endorsed termination in the 1950s, Utah’s Indians were prohibited by this state from voting into the 1950s, and afterward subjected to persistent voter suppression—the landmark 2018 Human Rights Commission voting rights settlement between San Juan County and the Navajo Nation as only the most recent example. The state has contested tribal sovereignty and resource decisions in an unbroken series of lawsuits since the 1960s, even up to its disputation of Bears Ears National Monument and tribal co-management with our public land agencies, echoing that forgetfulness that this was Native land before it was appropriated as federal and then coveted as state land.

So, from the perspective of Utah’s Native peoples, the meanings of statehood complicate an already fraught Indian-federal government-to-government relationship with a state layer of government looking to assert its authority. Thinking more broadly, one might extend that perspective to other racial and ethnic groups that have struggled to find an equal place in Utah under state law.

Remembering and forgetting also applies in the ways we commemorate our march to statehood as a struggle between Brigham Young and the federal government. Facing its own disestablishment due to polygamy and church control of local and territorial politics, the church’s compromise “Manifesto” and the “Americanization” of Utah seems revolutionary, a moment worth lamenting for some and celebrating for others. But what we forget is that statehood came and neither polygamy nor church hegemony actually ended.

What we forget is that statehood came and neither polygamy nor church hegemony actually ended.

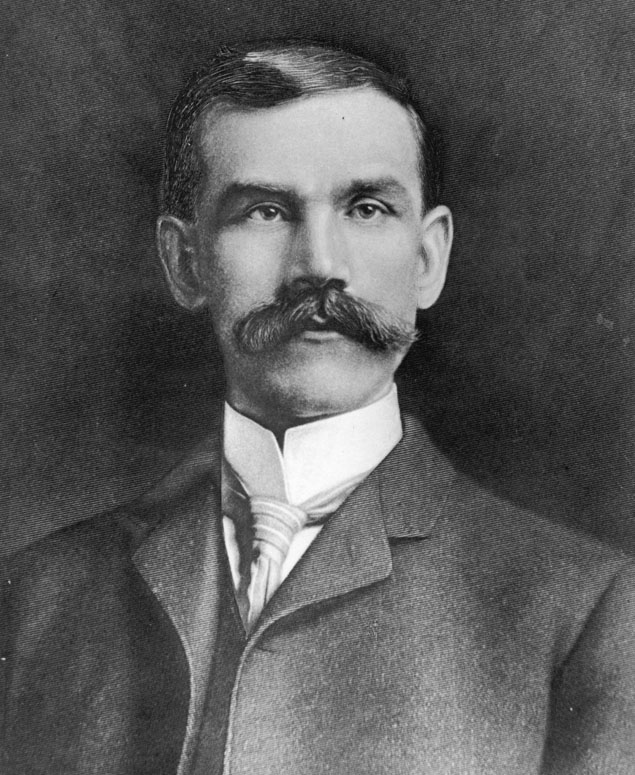

The truly revolutionary moment for Utah and the LDS church actually takes place a decade later, when the eyes of the nation once again lock on Mormon control of politics and polygamy in the guise of Senator and LDS apostle Reed Smoot. Congress threatens the church with disestablishment and Utah with a return to the territorial “kids table.” It’s in the wake of this that LDS president Joseph F. Smith leads the church (and in effect the entire state) through a major political, economic, and theological transformation in order to hold on to statehood—from Mormon Democrats to Utah Republicans; from agrarian communalism and separatism to corporate capitalism and nationalism; from polygamy to eternal marriage, deification to perfection, vengeance to reconciliation, gathering to international growth. As the historian Kathleen Flake and the geographer Ethan Yorgason point out, this second moment of statehood is the commemorative watershed where church authority in daily life faded, even as church leaders exercised new sources of power to maintain religious group identity; where Mormons and non-Mormons re-balanced political power based on economic self-interest and class; where Utah as a state and Mormonism as a religion took on its conservative mantle to appear like and reassure the rest of the nation it belonged.

So, those are two different ways of thinking about the meanings of statehood that reach far beyond the political moment of 1896 itself, recognizing continuation over culmination, and how our commemorations are about forgetting as well as remembering in service to the present.