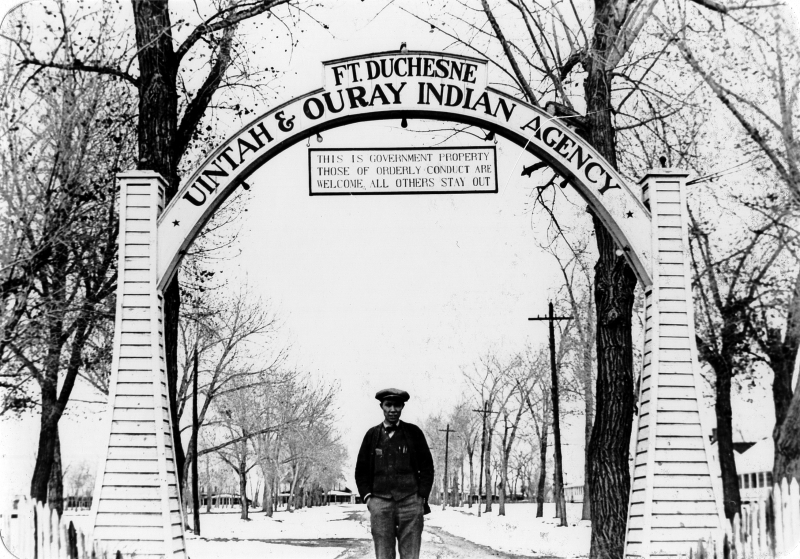

Buffalo Soldiers practicing military maneuvers at Fort Duchesne in 1910. Credit: Courtesy of the Uintah County Library Regional History Center

Fort Duchesne

Utah's Cultural, Racial, and Religious Diversity in the 1890s

At the time of statehood, Utah was home to a rich variety of cultures that intersected and overlapped through a multitude of social, religious, and economic connections. Through these connections, communities formed. They highlighted the similarities and differences among the personal lives of Utahns of the day.

Utah's Cultural Groups

Rapid Population Rise

During the last decade of the 19th century, Utah experienced a sharp increase in population as a result of births and immigration.

The documented population of Utah jumped over the course of the 1890s. At the beginning of the decade the population was recorded as 210,779 and by the end it had reached 276,749.

Utah's Many Cultural Indentities

Within each of Utah’s cultural groups, there were also further distinctions, as there are in many cases to this day. For instance, Italian immigrants from the Tyrolean region differentiated themselves from those who were born in Calabria, and the Capote Ute band identified separately from the Mouache band.

Navajo

Japanese

Shoshone

Italian

Jewish

Latino

Paiute

Catholic

Samoan

Goshute

Hawaiian

Ute

Chinese

Episcopal

Fort Duchesne

A Microcosm of Utah in the 1890s

In the late summer of 1886, construction of Fort Duchesne began. The physical presence of the fort initially consisted of canvas tents and hastily constructed temporary wooden structures, which contributed to the harshness of the first winter, but by the summer of 1888, most of the temporary structures had been replaced by permanent ones. The grounds eventually included a canal, grandstand, and picket-fence-surrounded buildings. The logistics of the project were complex. All of the building material had to be transferred dozens of miles by cart from the nearest railway station in Price, making the fort one of America’s most expensive to construct.

An economy quickly developed around Fort Duchesne. Local farmers sold livestock and produce to soldiers, and new service and construction jobs emerged around the day-to-day activities of the fort. The fort hospital treated both soldiers and civilians, and the post office received daily deliveries, including newspapers, starting in 1889.

The Communities of Fort Duchesne

Ute Communities

The fort had an unequal relationship with the nearby Ute communities because its soldiers were tasked with overseeing the reservation. At times, this arrangement helped the Ute communities. It offered them a certain level of protection from outside communities, but it also meant they were policed by the soldiers. Ute bands benefited from goods and services provided by the fort and the surrounding economy, but because their movement off the reservation was restricted, these benefits were more or less compulsory.

Buffalo Soldiers

For most of its existence, the fort was staffed by Buffalo Soldiers from the 9th Cavalry, an all-Black regiment and the first unit in the country to have Black commanding officers. They were stationed at Fort Duchesne from September 1892 to March 1901 apart from a brief few months in 1898 during the Spanish-American War. Their duties involved policing the reservation and surrounding areas, accompanying agents as they delivered annuities, and adhering to a strict routine of watches and drills. During fatigue duty, they repaired roads, worked at the fort’s sawmill, and did odd jobs around the fort. In their off time, they enjoyed hunting and fishing. It was a relatively calm placement for the soldiers, but the geographic isolation of the fort led to loneliness among many of the men.

Chinese Immigrants

Many Chinese men immigrated to the American West in the middle of the 19th century to work in railroad construction. They were welcomed in large numbers for these projects, but once the Transcontinental Railroad and other major lines were completed, racist attitudes among white settlers began to surface. Native American groups who had at first welcomed Chinese immigrants came to regard them with disdain. The passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act cemented these opinions into law by limiting immigration from China. The act only allowed relatives of men who were currently living in the United States to enter the country. Through falsified documents showing their familial ties to previous immigrants, some “paper sons” and “paper daughters” managed to enter the country under assumed identities.

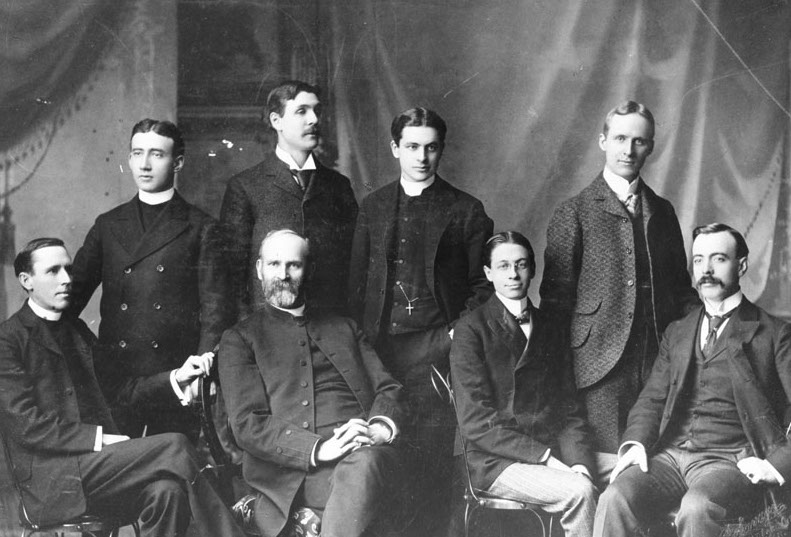

Episcopal Missionaries

Many Christian denominations sought to prosthelytize the Native Americans living in Utah. In order to limit the competition among these denominations, Congress determined that each Native American reservation should be assigned its own church. The residents of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, whose agent was the Episcopalian Colonel J. F. Randlett, chose the Episcopal Church. Throughout the 1890s, a handful of missionaries established churches and assistance programs in Leland (now called Randlett) and Whiterocks.

In 1894, Archdeacon Frederick W. Crook was invited by Colonel Randlett to perform the first Episcopal service at Fort Duchesne. Using language more conventional of the day, he noted the unique diversity of the service.

The language and terminology used in the historical materials below reflect the context and culture of their creators, and may include language that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate, or not appropriate for all ages.

“On Sunday, a most unique service was held in one of the large rooms. To the left sat a group of colored United States soldiers; in the center were the children of the Indian school, surrounded by bucks and squaws, with little papooses done up in those odd babyspoons, or baskets, clad in every variety, from buckskin to the vari-colored and thin calico, such as contractors only know how to sell. Around the priest were the white employees, with a few people from the Mormon settlement, present at the agency on trade, and attracted by the novelty. Six nationalities were represented.”

The expansion of places, like Fort Duchesne, seems to dissolve and adjust borders between cultural and geographic communities. Credit: “Float” by Sunny Belliston Taylor. Courtesy of the Utah Division of Arts & Museums. All Rights Reserved.

Closing the Fort

The End of the Fort but not the Community

Fort Duchesne continued to operate after the turn of the century, although talks of closing it had begun all the way back in 1891. The Indian Wars, as they were known, had spurred its creation, but as times changed, so did the fort's role.

In the end, the soldiers were removed in 1912, and the community shifted around this change in the economy. The buildings of the fort eventually came into the hands of the Ute Indian Tribe, and Fort Duchesne now exists as a civilian, primarily Ute, community

Legacy of Fort Duchesne

The mixture of voices at Fort Duchesne was common throughout Utah in the 1890s. All communities included diversity in terms of age, race, gender, religion, or culture. Around us, we see a similar multitude of voices in Utah today.